You Know Sink the Maine Again or Something Jfk

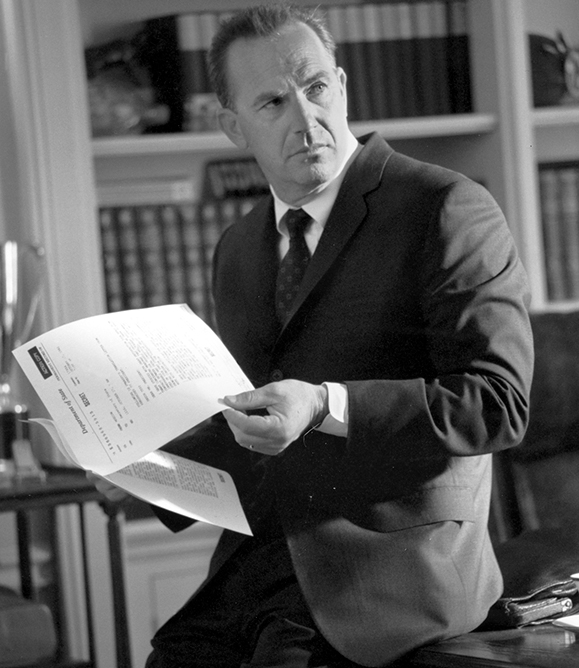

Bruce Greenwood equally John F. Kennedy in Xiii Days.

On the morning of Sabbatum, October 20, 1962, I was in a station wagon with my family en road to Milwaukee's Billy Mitchell Field to hear President John F. Kennedy make a entrada speech for Democratic congressional candidates. As we moved slowly in a long line of cars to the drome, the radio reported that JFK had come up downward with a "slight cold" in Chicago and was returning directly to Washington. We didn't know then that the Cuban Missile Crisis was reaching its humid point.

Even later on Kennedy revealed in a tv address ii days afterward that the U.S. and the USSR were staring each other down over nuclear missiles in Cuba, I don't remember being worried almost the possibility of world annihilation. Every bit a devout Cosmic male child, I was more often than not concerned that the president had lied to the states. My naïveté over what the French phone call a "cold diplomatique" is a measure of how far we've come since that more innocent era; today we tend to assume the president is lying unless we can be convinced otherwise.

The stirring new film about the Missile Crunch, 13 Days, can't help seeming somewhat quondam-fashioned in stressing the importance of thoughtful presidential leadership. The crisis really had ii heroes: President Kennedy and Soviet Chairman Nikita S. Khrushchev. Their prior recklessness over Republic of cuba precipitated the crisis, only in the end both had the wisdom to salve the world from destruction. Khrushchev is not depicted in Xiii Days, but he is a powerful off-screen presence. In the 1974 TV movie on the crisis, The Missiles of October, he is memorably played by Howard da Silva.

Missiles is more than a chamber play than a realistic re-cosmos, but it works superbly on those terms while thereby fugitive the pitfalls of impersonating famous characters. Surprisingly, and then does the far more elaborately produced Thirteen Days, which boasts an extraordinarily fine operation past Bruce Greenwood as JFK. Greenwood captures Kennedy's body language and the timbre of his voice while avoiding the usual extravaganza. Most importantly, Greenwood conveys the thoughtfulness and prudence that enabled Kennedy to resist the pressures of his Joint Chiefs of Staff to escalate the crisis by attacking Cuba. 13 Days is unexpectedly timely now, since "thoughtfulness and prudence" are not words that leap to listen in discussing our new non-elected "president" George W. Bush.

Steven Culp smoothly impersonates Robert F. Kennedy in 13 Days, although the label is somewhat sentimentalized, portraying Bobby every bit less "ruthless" than he actually was, thus missing some of his complication. The film alludes only briefly to RFK's plotting confronting Castro, which continued even after the missile crisis, and while emphasizing his gradual dovishness, it does not include his rash suggestion early in the crisis that the U.S. stage a provocation, "[Y]ou know, sink the Maine again or something."

Both actors playing Kennedys human activity rings around the nominal star, Kevin Costnet, who affects a laughably bad Kennedy accent equally the president's date secretarial assistant, Kenneth O'Donnell. Costner doesn't seem to realize that a Kennedy accent, which has strong traces of England, is non the same every bit a Boston Irish gaelic emphasis. Despite Costner'due south efforts to be relatively self-effacing, his star power imbalances the moving picture, since his O'Donnell is basically a glorified courtier. But it was only Costner'due south clout as star and producer that made this motion picture possible. (The unofficial sequel to Xiii Days has already Ken made, and it likewise stars Costner – Oliver Stone'southward JFK. Peradventure side by side he can play George H. W. Bush-league in the prequel, The Bay of Pigs.)

Thirteen Days screenwriter David Self ably edited the riveting dialogue derived from the 1997 volume of transcripts of the White Firm deliberations, The Kennedy Tapes, edited by Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow.

Unfortunately, that marvelous book is given ungenerous acknowledgment in microscopic blazon near the close of the terminate credits (the film's title is cribbed from RFK's posthumously published book on the crisis, on which The Missiles of October was based).

Director Roger Donaldson, an Australian who began his filmmaking career in New Zealand, is not seduced by whatsoever American flag-waving rhetoric, and he vividly depicts the ominous war machine preparations for an invasion of Republic of cuba, an chemical element unseen in Missiles. But 13 Days, for all its aura of authenticity, misses the ultimate point of the crunch. The filmmakers went eyeball to eyeball with some of the darkest troths near modem American history – and they blinked.

The strange decision to tell the story from O'Donnell's viewpoint led Kennedy speechwriter Theodore Sorensen to mock Thirteen Days as "Kenny O'Donnell saving the world." Journalist and Kennedy confidant Ben Bradlee described Costner'south heart-tugging portrayal of O'Donnell as "exaggerated and fictionalized. To me, he was the enforcer, he kept everyone in line. He was a tough guy and totally loyal servant and friend." It'south pregnant that the more convivial Kennedy aide Dave Powers, JFK'south closest friend and O'Donnell's collaborator on the 1972 memoir Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye, is not portrayed in the film, for Costner'south character resembles a combination of Powers and O'Donnell.

I find it hard to accept O'Donnell as a loyal, sympathetic figure considering I tin't overlook his role in roofing upwards the truth about Kennedy's assassination. O'Donnell and Powers were riding in the Cloak-and-dagger Service follow-up automobile behind JFK's limousine in Dallas on Nov 22, 1963. Asked by Warren Commission assistant counsel Aden Specter for his "reaction equally to the source of the shots," O'Donnell testified cryptically, "My reaction in function is reconstruction – is that they came from the right rear. That would be my best judgment." However, Business firm Speaker Thomas P. (Tip) O'Neill revealed in his 1987 autobiography, Man of the House, that O'Donnell and Powers told him they heard 2 shots from backside the picket fence on the grassy knoll in front end of the president.

O'Donnell explained to O'Neill, "I told the FBI what I had heard, only they said it couldn't have happened that mode and that I must accept been imagining things. So I testified the fashion they wanted me to. I merely didn't want to stir up any more pain and trouble for the [Kennedy] family." Powers more truthfully told the commission, "My starting time impression was that the shots came from the right and overhead, only I also had a fleeting impression that the noise appeared to come up from the forepart in the area of the triple overpass. This may accept resulted from my feeling, when I looked forward toward the overpass, that we might accept ridden into an ambush."

Thirteen Days is most valuable for reopening for a wide audience the question of noncombatant control of the military, a topic equally important today as it was in 1962. The heart of the moving-picture show is JFK's confrontation with his Joint Chiefs, particularly General Curtis LeMay, who at the time was U.Due south. Air Strength chief of staff. Not content with incinerating cities in Germany and Japan during Earth War Two, LeMay after headed the Strategic Air Control and wanted to launch a preemptive nuclear attack against the USSR. He helped inspire not one but two characters in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove, Sterling Hayden'due south General Jack D. Ripper and George C. Scott's Full general Buck Turgidson.

The most stunning revelation in The Kennedy Tapes is the exchange betwixt LeMay and JFK on October 19, which is recreated on screen. The insubordinate general angrily reminded Kennedy that "nosotros made pretty stiff statements well-nigh the [unclear] Cuba, that nosotros would take action against offensive weapons. I call back that a blockade, and political talk, would be considered by a lot of our friends and neutrals as being a pretty weak response to this. And I'm sure a lot of our ain citizens would feel that way, too. You're in a pretty bad ready, Mr. President."

Kennedy responded incredulously, "What did you say?"

LeMay repeated, "Yous're in a pretty bad ready."

The Kennedy Tapes reports that Kennedy then made "an unclear, joking, reply." According to RFK's Xiii Days, which incorrectly ascribes LeMay'due south remark to some other full general, the president retorted, "You lot are in it with me." The film's JFK says, "Well, perhaps y'all haven't noticed you're in it with me." The parting LeMay (played past Kevin Conway) fumes, "Those goddam Kennedys are gonna destroy this country if we don't practise something about this." No wonder the actual President Kennedy worried at i bespeak in that crisis, "Suppose Khrushchev has the same degree of control over his forces as I have over mine?"

Khrushchev's own anxiety over the situation, expressed in his moving letter to Kennedy on October 26, receives insufficient emphasis in the motion picture. The Soviet leader wrote: "If yous have not lost control of yourself and realize conspicuously what this could atomic number 82 to, and so, Mr. President, yous and I should not now pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied a knot of war, because the harder y'all and I pull, the tighter the knot will become. And a time may come when this knot is tied so tight that the person who tied information technology is no longer capable of untying it, and then the knot will accept to be cut. What that would mean I need not explain to you, because yous yourself understand perfectly what dread forces our ii countries possess."

Secretary of Country Dean Rusk'southward famous annotate, "We are eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow simply blinked," referred to the Soviets, but he could accept been describing JFK's human relationship with the Chiefs. After Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles in exchange for a secret bargain to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey and a promise not to invade Republic of cuba, Kennedy wrote him, "I call back that you and I, with our heavy responsibilities for the maintenance of peace, were aware that developments were approaching a point where events could have go unmanageable."

The turning indicate of the crunch was Robert Kennedy'due south meeting with Soviet Administrator Anatoly Dobrynin on October 27, delivering an ultimatum from the president while offering the other terms as olive branches. As reported by Khrushchev in his 1970 autobiography Khrushchev Remembers, the scene was considerably more than dramatic than the ane in the film, which chickens out at this critical moment of revelation past having Dobrynin, not RFK, bring upwards that some in the U.S. military "wish for war."

According to Khrushchev, what RFK told Dobrynin was: "The President is in a grave situation, and he does non know how to get out of it. We are under very severe stress. In fact We are under pressure from: our military machine to employ forcefulness against Cuba…Even though the President himself is very much against starting a war over Cuba, an irreversible chain of events could occur against his will. That is why the President is highly-seasoned straight to Chairman Khrushchev for his assistance in liquidating this conflict. If the situation continues much longer, the President is not sure that the military will not overthrow him and seize power. The American regular army could get out of control."

Kennedy's friend Paul B. (Reddish) Fay Jr., the nether secretary of the navy, had a similarly spooky conversation with JFK in the summer of 1962. Information technology took place the day subsequently Kennedy finished reading Seven Days in May the popular novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles West. Bailey Two near an attempted military coup against a fictional president. "It's possible," Kennedy told Fay. "Information technology could happen in this country, but the conditions would have to be just correct. If, for example, the land had a young President, and he had a Bay-of Pigs, at that place would be a certain uneasiness. Mayhap the military would do a petty criticizing behind his dorsum, but this would exist written off equally the usual military dissatisfaction with noncombatant control. Then if there were another Bay of Pigs, the reaction of the country would be, `Is he besides young and inexperienced. The military would about experience that it was their patriotic obligation to stand up set up to preserve the integrity of the nation, and only God knows just what segment of commonwealth they would be defending if they overthrew the elected establishment.

"Then, if there were a third Bay of Pigs, it could happen." Kennedy added defiantly, "But it won't happen on my watch. He felt so strongly about Such a threat that he regarded Seven Days in May as "a alert to the nation" and in 1963 immune director John Frankenheimer to shoot scenes for the film version in the White House. A full-folio advertisement for the film appeared in. the New York Times on the twenty-four hour period of the president's assassination.

The American public, unaware of the trade of the missiles in Turkey, generally considered the Cuban Missile Crisis an unalloyed Kennedy triumph, only from the viewpoint of the Chiefs information technology was a failure of presidential will, "some other Bay of pigs." Quondam Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recalled in 1987, "After Khrushchev had agreed to remove the missiles, President Kennedy invited the Chiefs to the White House then that he could thank them for their back up during the crisis, and in that location was 1 hell of a scene. LeMay came out proverb, `Nosotros lost! We ought to just go in there today and knock `em off.'"

Some have suggested that the nuclear test ban treaty with the USSR in. 1963 may have been regarded by military leaders as the "third Bay of Pigs," requiring a trigger-happy seizure of power to ensure U.S. superiority over the USSR. LeMay was not lonely in his advocacy of a first strike. At a July 1961 meeting of the National Security Council, the Chiefs outraged JFK with a presentation suggesting that the rates of missile product in the two countries would allow a "window of opportunity" in "late 1963" for a "surprise" U.Southward. nuclear attack on the USSR.

Kennedy's well-nigh eloquent statement on the danger of nuclear war was his speech at American Academy in Washington on June 10, 1963, which Khrushchev described every bit the greatest speech ever given by an American president. Part of that speech is played over the catastrophe of Thirteen Days: "What kind of a peace practice nosotros seek? I am talking nigh genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living. Not merely peace in our time, simply peace in all fourth dimension. Our problems are human being-made; therefore they can be solved past man…. For in the final analysis, our most basic mutual link is that we all inhabit this small planet. Nosotros all breathe the same air. Nosotros all cherish our children's futures. And nosotros are all mortal."

Khrushchev was equally eloquent when he reflected to Norman Cousins shortly after the crisis, "What good would it have done me in the last hour of my life to know that though our great nation and the United States were in complete ruins, the national honor of the Soviet Union was intact.?"

Both leaders paid dearly for their principled restraint. Khrushchev was deposed past his Presidium colleagues in October 1964, eleven months after Kennedy was murdered. Indira Gandhi observed, "Kennedy died because he lost the support of his peers." Those who go on to believe that a coup d'état can't happen in this country are ignoring not only the truth well-nigh November 1963 but also the events surrounding our concluding presidential election. ♦

Source: https://www.irishamerica.com/2001/04/film-forum-jfk-vs-the-joint-chiefs-in-thirteen-days/

0 Response to "You Know Sink the Maine Again or Something Jfk"

Post a Comment